Im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué und andere bretonische Gelehrte wanderten zu sammeln und speichern die alten Lieder in der alten keltischen Sprache, die von der Französierung bedroht waren.

Einige von ihnen waren patriotische Lieder, deren Hintergrundgeschichte sich von Pfarre zu Pfarre, von Jahrhundert zu Jahrhundert, von Nachtwache zu Nachtwache, nach dem Abendessen in der Stille der Landschaft verbreitet hatte. Die Stille und Schönheit der Natur, Häuser und Menschen, in der bretonischen Welt, die in den Hof- und Kleinadelhaüsern überlebt hatte, übertrugen das Pflicht der Überlieferung, die schon seit lange her von den Fürsten Kleinbritanniens weggelassen war.

Hier das Lied Der Tribut des Newenoes, ist ein derjenigen, die die Identität der Brittonischsprecher zu halten geholfen, denn es erzählt ein tragisches Ereignis der ersten Jahrhunderte ihrer Präsenz auf dem Kontinent, während es auch den Glanz der vergangenen Geschichte des Volks erinnert. Dieses Lied wurde von der franz. Schriftstellerin Georges Sand mit Homers Ilias verglichen, das sie dem bretonischen Gesang noch unterlag.

Mit diesen gesammelten Liedern handelte es sich auch darum, die bretonische Musik zu bewahren, so verschieden von der modernen europäischen Musik , die ihre Spiritualität verloren hatte, denn sie war mehr darüber besorgt, die Menschen zu unterhalten als die Gedanken der Seele zum Ausdruck und hervor zu bringen. Die bretonische Zivilisation hatte die alten Formen behalten, in vielen Disziplinen, und die modale Musik war eine von ihnen. Deswegen würden daher die Modernen behaupten, dass die bretonische Kultur „im Rückstand“ geblieben sei, während sie tatsächlich ein Hindernis für die sogenannten „Lumiéres“ war, die versuchten, ihren Despotismus überall in Europa durchzusetzen: Frankreich, Preuße, Russland… Und zweifellos müssen wir im Zusammenhang mit diesem Kampf der Titanen alle Angriffe und Verleumdungen sehen, die Hersart de la Villemarqué und seine Arbeit erleiden mussten.

Aber ein Teil Europas wurde nicht getäuscht und konnte sich so wieder an die Genialität dieser an der Westspitze Europas sterbenden Nation erinnern, die Zeugnis des Lichtes und der Identität der selbst sterbenden alten Europa ablegte.

Wir stellen hier das Gedicht Der Tribut des Newenoes – bretonisch „Droukkinnig Nevenoe“ – vor, mit seiner deutschen Übersetzung in der rechten Spalte. Aber es ist selbstverständlich, dass eine gute Kenntnis der bretonischen Sprache notwendig ist, um die Tiefe dieses Gedichts wirklich zu erfassen. Aus der Sammlung von Pater Loeiz ar Floc’h (einem bretonischen großen Gelehrten und Dichter) ziehen wir diese wenigen vielsagenden Zeilen aus dem Vorwort:

„Im Mittelalter spielten die Harfenspieler der Bretagne eine so dominante Rolle, dass sie die Ausrichtung der europäischen Literatur beherrschten„

Le brasier des ancétres / Das Feuer der Ahnen – Loeiz ar Floc’h

Union Générale d’Editions 1977

Um das Gedicht Der Tribut des Newenoes auf Deutsch und auf Bretonisch zu lesen, klicken Sie bitte auf den folgenden Link:

Der Tribut des Newenoe

Wo Sie in dieser Übersetzung das Wort „Kriegsgeschrei“ lesen werden, können Sie es auch mit den Ausdrucken „Raus!“ oder noch „Enttappe!“ ersetzen.

************************************

Englisch

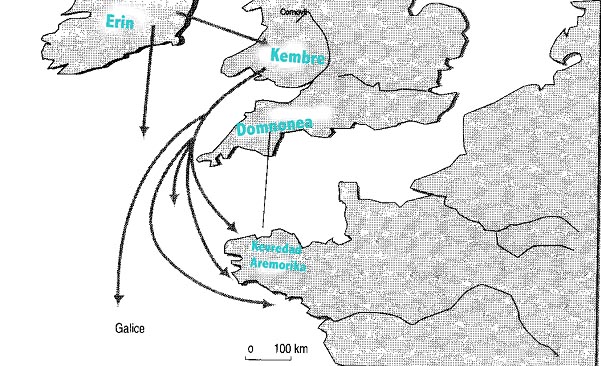

Barzaz Breiz (in modern spelling Barzhaz Breizh, meaning „Ballads of Brittany“: barzh is the equivalent of „bard“ and Breizh means „Brittany“) is a collection of Breton popular songs collected by Kervarker (Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué) and published in 1839. It was compiled from oral tradition and preserves traditional tales, legends and music. Hersart de la Villemarqué grew up in the manor of Plessix in Nizon, near Pont-Aven.

The book Barzaz Breiz brought Breton culture again into European awareness. Though Breton culture was known very early in Europe, during the middle ages.

The book was also notable for the fact that La Villemarqué recorded the music of the ballads as well as the words. This was one of the first attempts to collect and print Breton traditional music, except hymns.

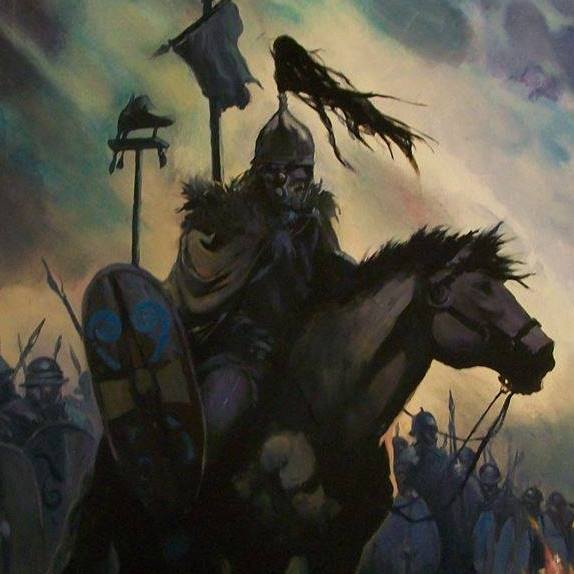

Here is the traduction of the poem Droukkinnig Nevenoe / Nominoe’s Tribute, wich tells about the early fights between the Breton and the French.

1. Gold herb (1) was mown by somebody.

For it has drizzled suddenly .

-Let’s fight!-

For it has drizzled suddenly.

2. „It drizzles, it drizzles“, has said

The chief, from the Mount of Arrée.

-Let’us fight!-

3. „For three weeks it has been misty,

Far towards the Frankish country,

4. So that by no means can I see,

If my dear son returns to me!

5. Merchant, who travels many lands,

Did you hear of Karo, my son?“

6. -Maybe, old father of Arrée,

But how looks he and what does he?

7. A man of sense, a man of heart

Who went to drive to Rennes the carts;

8. Who went to Rennes with the barrows

That horses bound three by three draw.

9. Well divided each cart carries

Brittany’s tribute faithfully.

10. Is your son the tribute-bearer?

You may wait for him no longer!

11. When they came to weigh the silver

There lacked 3 pounds in each hundred;

12. And the steward has said: „Your head,

Vassal, shall then complete the weight.“

13. And suddenly his sword he’s drawn

And cut off the head of your son!

14. And he has grasped it by the hairs

And he has thrown it on the scales

15. The old chief when he heard that news

Staggered and he was like to swoon.

16. Harshly upon the rock he fell

Hiding his face with his white hair.

17. And his head in his hands, he moaned:

„Karo, my son, my poor dear son!“

II

18. The great tribal chief has set out

And by his kindred he’s followed

19. The great tribal chief approaches

The house where Nominoë lives.

20. -Tell me, o head of the porters,

Is he at home now, the master?

21. -Be he there or be he not there,

God keep him always in good health!-

22. And he was still to him speaking

When the Lord came to his dwelling.

23. He was returning from the hunt

Preceded by great playful hounds

24. In his hand he held still his bow

On his shoulder carried a boar.

25. From the mouth of the beast fresh blood

Was flowing upon his white hand.

26. Hail to you, honest mountaineers!

First of all, to you, tribal chief:

27. What news are you bringing to me?

What do you want to know from me?

28. -If a law and a God there be;

Is there a chief in Brittany?

29. There is a God to my belief.

And if I can, there is a chief

30. In Brittany. -He who will, can!

And who can, drives away the Frank!

31. Drives him from his country away

Avenges it now and always,

32. Avenges who lives and who died,

And me and Karo, my dear child.

33. My poor son Karo, beheaded

By the excommunicated,

34. Beheaded in his prime, alas,

To balance the weight in the scales.

35. And the old man began to weep

And his tears flowed down his grey beard.

36. As the dew at the rising sun

On a lily flower they shone.

37. And the Lord when his tears he saw

Swore a terrible, bloody oath.

38. By this boar’s head and the arrow

Which has pierced it, I do swear now:

39. I won’t wash the blood from my hand

Before washing my country’s wound!

III

40. And chief Nominoë has done

What no chief did, but he alone:

41. He went with bags to the sea shore

And gathered pebbles more and more,

42. Pebbles as tribute to tender

To the bald emperor’s (2)steward.

43. And chief Nominoë has done

What no chief did, but he alone:

44. With polished silver has he shod

His horse, and with reversed shoes.

45. And chief Nominoë has done

What no chief did, but he alone:

46. For, Prince as he is, he has gone

To pay the tribute in person!

47. -Open wide the big gates of Rennes

That I make entry in the town,

48. With chariots full of silver

‚tis Nominoë who is there.-

49. -Alight, my lord, and come ahead

And leave your chariots in the shed

50. Leave to the equerry your horse

And come and have supper above.

51. Come to soup, to wash, first of all

Hear you them sound the water-horn ? (3)

52. -I will wash presently, my laird

When the tribute shall have been weighed

53. The first bag they had to carry

(And it was tied right properly)

54. The first bag they had carried down

Was of the weight agreed upon.

55. The second bag which they had brought

Also of a right weight was found.

56. The third bag they weighed: -Aha! ha!

Aha! ha! This weight is not right!-

57. When the steward heard it, he had

Extended his hand to the bag.

58. And quickly he had seized the cord

And to untie it endeavoured…

59. Wait a moment, Master Steward

I will cut it off with my sword.

60. Hardly had he finished these words

That his sword leaped from the scabbard,

61. And it struck close to the shoulders

The head of the double bent steward,

62. And that it had cut flesh and nerves

And beside one chain of the scales.

63. In the scale had fallen the head

And thus now the balance was made.

64. But behold the town in uproar:

-Come on, and stop the murderer!

65. -He flees, he flees, quick, torches bring!

Let us run quickly after him!

66. -Bring torches! And you will do right:

Frozen is the road, black the night!

67. But I greatly fear you will wear

Your shoes if follow me you dare,

68. Your shoes of blue gilded leather!

But your scales you will use no more;

69. Your golden scales in weighing stones

Brought as tribute by the Bretons.

-Let’s fight!-*

- Praised by George Sand as superior to the Iliad, this song was first published in „Barzhaz Breizh, 2nd edition, 1845.

- „I learnt this song from the singing of Joseph Floc’h, a farmer at Kergerez in the mountains“. (L.V. „argument“ in the 1846 edition).

In the 1867 edition, this information is replaced by the excerpts from Augustin Thierry’s books quoted hereafter. On the other hand the „argument“ to the next song, „Alan the Fox“ states that both ballads were sung by „an old peasant, who was a soldier in the army of Georges Cadoudal“.

This soldier was precisely called by name in the 1846 edition: it was „an old peasant, named Loéiz Vourriken from the parish Lanhuel-en-Arrée, who served in the days of his youth under Georges Cadoudal“.One may wonder if both these tales of the double beheading and of the sly fox do not apply to the Chouan uprising, since La Villemarqué has become less peremptory about the second song, as time went by: in 1846 he wrote: „The war cry you are about to read… refers to one of the two victories of Alan Twisted-Beard“. In 1867, the same sentence reads „…is likely to refer…“Francis Gourvil notes (p. 354) that a place-name „Kerguérez“ is found in the parish Leuhan where lived another(?) Floc’h, Michel, the singer of Arthur’s March.

1 The golden herb or „selagium“ is a magic herb that should never be cut with an iron blade which causes the sky to turn cloudy and a calamity to happen.

2 The Emperor Charles, surnamed the Bald.

3 Before the repast, at the sound of the horn, one washed one’s hands.

*************************************************

französisch:

Drouk-kinnig Nevenoe / Le Tribut de Nominoë

Au XIXe siécle, Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué* et d’autres parcouraient les campagnes du pays pour recueillir et ainsi sauver de l’oubli des chants dans la vieille langue celtique, dans une Bretagne qu’il voyait dejá en voie d’extinction.

Un certain nombre d’entre eux étaient des chants patriotiques, dont la trame de fond s’était colportée de paroisse en paroisse, de siécle en siécle, de veillée en veillée, aprés de souper dans le silence des campagnes. Le silence et la beauté de la nature, des maisons et des personnes, dans le monde breton qui avait survécu dans la discrétion des chemins creux, portaient au souvenir et au devoir de mémoire, chez un peuple de paysans et petits hobereaux abandonné de ses princes.

Ici, Le Tribut de Nominoë, est l’un de ceux qui contribua á maintenir l’identité des brittophones, relatant un épisode tragique des premiers siècles de leur présence sur le continent, en même temps qu’il rappelle la gloire des faits passés. Ce chant fut comparé par Georges Sand à l‘Iliade d’Homère, qu’elle jugeait même inférieur au chant breton.

Dans ces chants collectés, il s’agissait aussi de conserver la musique bretonne, si différente de la musique européenne á la méme époque, qui avait perdu de sa spiritualité, préoccupée qu’elle était plus de divertissement qu’émettrice et inspiratrice des pensées de l’âme. La civilisation bretonne avait gardé les formes anciennes, et cela dans beaucoup de disciplines, la musique modale en faisant partie. Ce qui fera dire par les modernes que cette culture était „retardée“, alors qu’elle était en fait un barrage aux prétendues „Lumiéres“ qui tentaient d’imposer leur despotisme partout en Europe. Et c’est sans doute dans le cadre de ce combat de titans qu’il faut voir comprendre toutes les attaques et calommies que durent endurer Hersart de la Villemarqué et son oeuvre.

Mais une partie de l’Europe de s’y est pas trompée, et a pu ainsi de souvenir á nouveau du génie de cette nation, gisant á l’agonie en sa pointe occidentale, lumiére et mémoire de la vieille Europe, celle-ci méme sur son lit de mort.

Nous présentons ici le poéme „Droukkinnig Nevenoe“ tel qu’on peut le lire dans le recueil de l’abbé Loeiz ar Floc’h, avec sa traduction française. Mais il va sans dire qu’une bonne connaissance de la langue bretonne est indispensable pour saisir vraiment la profondeur de ce poème. C’est de ce méme ouvrage que nous tirons ces quelques lignes évocatrices de la préface:

„Au Moyen-Age, les harpeurs de Bretagne ont joué un rôle si prépondérant qu’ils ont gouverné l’orientation des littératures européennes„.

(Le brasier des ancétres – Loeiz ar Floc’h

Union Générale d’Editions 1977)

Cliquez ici pour lire le poéme Drougkkinnig Nevenoe / Le Tribut de Nominoë

Drouk-kinnig Nevenoe

*

version avec traduction en allemand:

Der Tribut des Newenoe

* Das Jahr 1839 wurde für die bretonische Sprache und Literatur ein Schlüsseljahr, denn in diesem Jahr veröffentlichte der Sprach- und Altertumswissenschaftler Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué (1815 – 1895) aus Kemper (Quimper) unter dem Titel „Barzaz-Breiz“ zum ersten Mal eine Sammlung bretonischer, bis dahin nur mündlich überlieferter Volkslieder, Erzählungen und Legenden. Hersart de La Villemarqué, der auch korrespondierendes Mitglied der Berliner Akademie der Künste war, veröffentlichte diese Sammlung auf Bretonisch mit französischer Übersetzung. Das „Barzaz-Breiz“ erreichte – der romantischen und zeitgenössischen Neugier auf „ländliche Kultur“ folgend – eine große Verbreitung und machte die bretonische Volkskultur erstmals auch weit über Frankreichs Grenzen bekannt: schon 1858 erlebte es unter dem Titel „Bretonische Volkslieder“ eine Übertragung ins Deutsche.

* Das Jahr 1839 wurde für die bretonische Sprache und Literatur ein Schlüsseljahr, denn in diesem Jahr veröffentlichte der Sprach- und Altertumswissenschaftler Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué (1815 – 1895) aus Kemper (Quimper) unter dem Titel „Barzaz-Breiz“ zum ersten Mal eine Sammlung bretonischer, bis dahin nur mündlich überlieferter Volkslieder, Erzählungen und Legenden. Hersart de La Villemarqué, der auch korrespondierendes Mitglied der Berliner Akademie der Künste war, veröffentlichte diese Sammlung auf Bretonisch mit französischer Übersetzung. Das „Barzaz-Breiz“ erreichte – der romantischen und zeitgenössischen Neugier auf „ländliche Kultur“ folgend – eine große Verbreitung und machte die bretonische Volkskultur erstmals auch weit über Frankreichs Grenzen bekannt: schon 1858 erlebte es unter dem Titel „Bretonische Volkslieder“ eine Übertragung ins Deutsche.